Introduction and Motivation:

When developing cross-platform modular software applications, interoperability is essential to ensure easy interaction between different components of an application even if they were implemented in different programming languages. This is where inter-process communication technologies come in action to enable parallel processing and share of data between processes running either locally on same machine or distributed across a computing cluster.

Multiple inter-process communication frameworks / libraries already exist, each with its own architecture, performance and support of wide range of programming languages. Example libraries that I came across my working journey are: gRPC (an open-source remote procedure call framework developed by Google) and ZeroMQ (a flexible asynchronous messaging library designed for use in distributed or concurrent applications).

Nevertheless, I was always curios about OS built-in communication mechanisms (i.e, at the end of the day an operating system is a set of components and services that need to interact with each other according to some standard). In addition, I came across certain scenarios where using an external communication library was an 'overkill' for the problem at hand.

In the context of Windows, Component Object Model (COM) is Microsoft inter-process communication component that is built in the native Windows API facilitating interaction between software objects that implements one or more interfaces. These objects can be within a single process, in other processes, even on remote computers.

In this blog-post, I want to share my initial experience working with COM objects using Python. This can help creating Python applications that can talk and reuse functionality from Windows applications written in .NET / C++ and expose their features via COM interface.

About COM (Component Object Model):

According to Microsoft, COM is an object-oriented system for creating binary software components that can interact. It is the foundation for Microsoft's OLE (Object Linking and Embedding) technology which allows Microsoft Office applications to communicate and exchange data between documents (e.g, embedding an Excel chart inside a Word document)

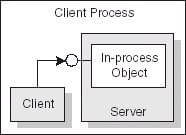

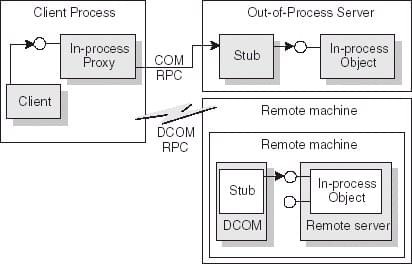

Through COM, a client object can call methods of server objects, which can be Dynamic Link Libraries (DLLs) or executables (EXEs). Remote COM execution is possible by using Distributed Component Object Model (DCOM) which exposes application objects via remote procedure calls (RPCs)

In-Process and Out-Of-Process COM:

|

| Credits: docwiki.embarcadero.com |

|

| Credits: docwiki.embarcadero.com |

DLL Surrogates:

COM Server - Client example in Python:

You can write COM based applications in multiple programming languages. The most common combination I have seen is C++ and C# with Visual Studio IDE providing a starting template for development. Here I want to explore however the extension of COM development into Python world.

- Install Python 3.9 or higher to work with comtypes

- Start a Python virtual environment with: python -m venv venv

- Activate the virtual environment: . venv/Scripts/activate

- Install comtypes with: python -m pip install comtypes

- Windows Kits version 10 and above need to be installed using Visual Studio Installer

Creating and registering COM server in Python:

To implement a COM server object in Python we first need to create a type library file using IDL (Interface Definition Language) syntax. This file provides the COM interface attributes along with the definition of derived classes and their methods. Every type library / interface / class defined needs to be labelled with a unique GUID. An example IDL file syntax is provided below which defines a COM interface named: "IMyCOMInterface" with a derived class: "MyCOMObject" that has the method: "MyCOMMethod"

import "oaidl.idl";

import "ocidl.idl";

[

uuid(FFE9DC12-DF9B-4B3A-896D-14556FFC59E6),

dual,

oleautomation

]

interface IMyCOMInterface : IDispatch {

HRESULT MyCOMMethod([in] INT a, [in] INT b, [out, retval] INT *presult);

}

[

uuid(61CAA54D-F3C7-442D-9827-BEB160D13134)

]

library MyCOMLib

{

importlib("stdole2.tlb");

[uuid(BC2ED72E-ACC6-4A0D-9DC3-C9767658A6CA)]

coclass MyCOMObject {

[default] interface IMyCOMInterface;

};

};Next we need to compile the IDL file to generate the required .(tlb) type library file. To do so, we trigger the MIDL compiler on the IDL file. The compiler should be automatically installed as part of Widnows Kits (SDKs) installation. The compiler will not be present on system path by default so you need to add it manually or run it from a Visual Studio Developer Command Prompt.

|

| Compiling COMServer.idl using MIDL compiler |

Once the compilation process succeeds, the COMServer.tlb binary file is generated along with a couple of C header and source files.

| Generated artifacts from compiling COMServer.idl file |

Now we can move to Python and start implementing "MyCOMObject" class followed by the registering of the COM object in Windows registry. The code snippet below outlines the implementation:

import comtypes

import comtypes.server.localserver

from comtypes.client import GetModule

import os

# generate wrapper code for the "MyCOMLib" library, this needs

# to be done only once (but also each time the IDL file changes)

GetModule(r"./COMServer.tlb")

from comtypes.gen.MyCOMLib import MyCOMObject

class MyCOMObject(MyCOMObject):

# COM object attributes that will reside in registry entries

_reg_threading_ = "Both" # ThreadingModel for execution: "Both", "Free", or "Apartment"

_reg_progid_ = "MyCOMLib.MyCOMObject.1" # programmatic identifier that can be associated with a CLSID

_reg_novers_progid_ = "MyCOMLib.MyCOMObject"

_reg_desc_ = "AK-Experiments COM server for testing"

_reg_clsctx_ = comtypes.CLSCTX_INPROC_SERVER | comtypes.CLSCTX_LOCAL_SERVER # contexts the COM server can operate within (e.g. inprocess, local server)

_regcls_ = comtypes.server.localserver.REGCLS_MULTIPLEUSE # controls the type of connections to a class object (e.g single, multiple .. etc)

print(f"COM-Server: Creating an instance of MyCOMObject. Server Process ID: {os.getpid()}")

def MyCOMMethod(self, a, b):

# COM method high level implementation in python

print("COM-Server: MyComm Method got Called")

return a + b

if __name__ == "__main__":

from comtypes.server.register import UseCommandLine

# invoke command line interface with a specific sys command to trigger register, unregister of COM server

# NOTE. You need admin access to perform registry operations

UseCommandLine(MyCOMObject)To register the COM server object, we trigger the above python script with the "/regserver" option from an elevated terminal:

To make sure the COM object is correctly registered, we can use tools such as OleView and COMView to find our COM object using its name of defined CLSID and check its properties and available interfaces. As you can see our COM object exposes correctly our defined "IMyCOMInterface" in addtion to other default interfaces. We can instantiate an instance of the COM server as well by the same tool as shown below and view properties and methods of underlying objects.

|

| Finding the COM object by its CLSID in OleView |

|

Creating an instance of MyCOMObject and calling MyCOMMethod in ComView |

Talking to the COM server from Python:

To communicate with the previously created COM object, we simply have to create an instance of the COM object with the aid of comtypes as follows:from comtypes.client import CreateObject

import os

def main():

# instantiate object using its programmtic ID or CLSID

# by default the context enumeration CLSCTX_SERVER : (CLSCTX_INPROC_SERVER | CLSCTX_LOCAL_SERVER | CLSCTX_REMOTE_SERVER) is used

com_object = CreateObject("MyCOMLib.MyCOMObject")

print(f"COM-Client: Created COM object: {com_object} from Client, Process ID: {os.getpid()}")

ret = com_object.MyCOMMethod(1,2)

print(f"COM-Client: Calling COM object MyCOMMethod with arguments 1 , 2 returns: {ret}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Upon running the above code we should be able to create an instance of the com server, get a pointer to the interface instance and then call the server implemented "MyCOMMethod" with two integers and get the correct sum as shown below:

You would also notice that I printed the process ID from which the server and client are running and in this case both are running from the same space as the IDs are identical so we can say that our COM server operates in "in-process" mode. If we run the same script above using a 32-bit (x86) Python virtual environment, you will notice that a new window pops up and the server starts in a separate process as the client. This can be confirmed by noting the different process IDs printed from client and server windows.

In this case, the COM server operates in "out-of-process" mode due to the bitness different between the client and the registered COM server. We can also enforce "out-of-process" behavior from the client side by passing the "CLSCTX_LOCAL_SERVER" context enumeration to the "CreateObject" method.